Record of Observation or Review of Teaching Practice

Session/artefact to be observed/reviewed: Costume Workshop – Sculptural Skeletons and Structures (part 1)

Size of student group: Approx. 10 students

Observer: John O’Reilly

Observee: Florence Meredith

Note: This record is solely for exchanging developmental feedback between colleagues. Its reflective aspect informs PgCert and Fellowship assessment, but it is not an official evaluation of teaching and is not intended for other internal or legal applications such as probation or disciplinary action.

Part One

Observee to complete in brief and send to observer prior to the observation or review:

What is the context of this session/artefact within the curriculum?

This is a session which is open to any student enrolled on BA(Hons) Performance: Design Practice, as a standalone workshop. However, it has been specially flagged to stage students who are participating in an elected project called We Move next term (unit 8), for whom the approaches and content introduced to them in these workshops will become relevant.

How long have you been working with this group and in what capacity?

This workshop is the first part of two parts – the group will be made up of learners at different stages of their academic journey, who are coming together as a unique group for this specific occasion. I regularly support some of these students in the open access costume studio space, and/or have led costume workshops they have attended in the past year. I have never worked with others.

What are the intended or expected learning outcomes?

Across these two workshops, we will explore different materials and techniques that can be used to create structure on and around the performing body – responding to, extending, or exaggerating the form. Participants will develop tools which enable them to investigate and recognise the qualities of structural costume materials, their creative potential, and what they need to consider in their application.

What are the anticipated outputs (anything students will make/do)?

Students will actively experiment with selected materials, draw structural diagrams, then collaboratively design and create a wearable, kinetic mock-ups within in a limited timeframe.

Are there potential difficulties or specific areas of concern?

The uncertainty of who will or won’t attend – and consequently the unpredictable levels of costuming ability, how many materials will be required, and how long parts of the session will take. The pacing of this workshop, which I have not delivered before – some sections make take more of less time than I anticipate.

How will students be informed of the observation/review?

I will email them ahead of time, and verbally tell them at the top of the session.

What would you particularly like feedback on?

Does the session sustain clarity in its aims, objectives and outcomes? Is it over-complicated?

How will feedback be exchanged?

Written, and/or verbally

Part Two

Observer to note down observations, suggestions and questions:

Pedagogy of the senses

The class preparation has been done in forensic detail – forensic in terms of care and attention to details but also in the sense that this class is about the signs and clues of materials which help fashion students understand how they might be used. It is an ingenious pedagogy by Flo which blurs the knowledges and disciplines of science and fashion, chemistry and craft.

A large square table around which the whole group will sit is laid out with materials for each individual students – coloured pencils, black cloth, thin strips of hard material and A3 paper – like a table setting for dinner

It can be useful to create a sense of belonging in a class through reference to a popular event, and Flo instigates a discussion about the award-winners for costume design in the previous evening’s BAFTAs. Equally, Flo’s version of the ‘icebreaker’ also enables people to bring something of themselves into the classroom, asking each person ‘what is your favourite material?’

Flo’s icebreaker is a reminder that what often works for student engagement is a task that gets them to bring something of themselves to the class – in this case along with disclosing their material choice they bring maker-intelligence in asking them also to discuss their preference. The range of materials cited by students is a tacit way of highlighting diversity in the room – Flo’s opening strategies create a positive atmosphere and a sense of purpose and learning.

Flo contextualises the workshop in terms of future units, then specifying that the session’s focus on the moving body and kinetic structures. The session is a sequence of exercises asking students to use their senses to identify the property of materials and what they may be used for.

The first exercise uses the black cloth as a blindfold, helping students focus on the feel and touch of the material. The students bend, feel, run their fingers across the strips, sensing how heavy or light it is. Flo directs students to “write down or draw the qualities you sensed in experimenting with the material”. This is their ‘data sheet’. It is such a nice idea naming this sensing as ‘data’ and perhaps that concept of data as something that is sensed could be something that could be explored a little more in class. Flo gives time for students to pause, gather their thoughts and feelings, draw and write, identifying the material and sharing ideas. There is a rhythm to this pedagogy that Flo is confident and skilful with.

For the next part Flo asks the students to explore the material further, “see what you can do with it.’ Students engage in different explorations and experiments with each material: dropping it in water; another tries to cut the material; someone else irons; another is bending it. Flo encourages everyone to use the room and material to make something. This guides students to different ways of knowing, and they are very engaged – perhaps this tacit practice and skill they are engaged in could be made more explicit?

It’s an all-round meaning-making activity where each student is working out an understanding for themselves of the material property and its possible use, while sense-checking themselves through the data gathering and the conversations with each other.

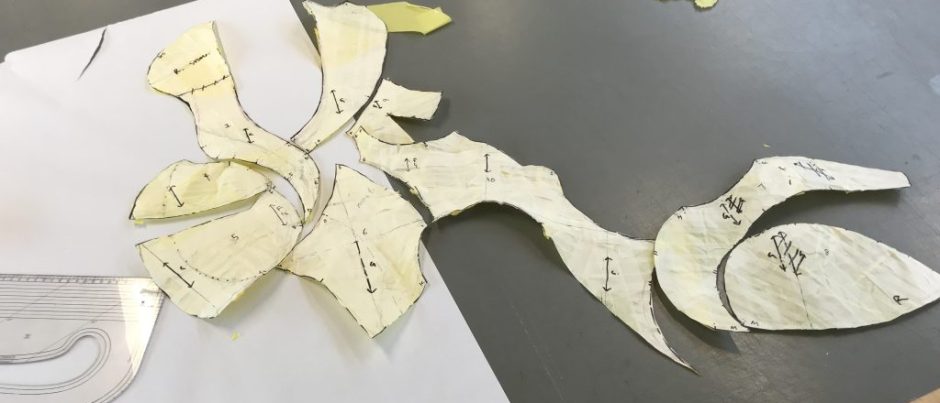

Each task brings knowledge forward from the previous one and for the final part of this workshop, Flo puts objects on the table and asking students to think about structure – the to create a diagram, thinking about its skeleton. Students work out with each other different ways of representing structure, some of this sense of know-how comes from the earned confidence of the session.

A lesson I took from Flo’s practice is that this pedagogic creativity and complexity is possible with clear planning, organisation and the trust of the teacher in the knowledges and skills brought by the students.

#materials #sensoryknowing #documentation

FYI

Orr, S., & Shreeve, A. (2017) ‘Teaching practices for creative practitioners’, Art and design pedagogy in higher education: Knowledge, values and ambiguity in the creative curriculum. Taylor and Francis Group

Makovicky, N. (2010) ‘“Something to talk about”: notation and knowledge-making among Central Slovak lace-makers’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 16.

Part Three

Observee to reflect on the observer’s comments and describe how they will act on the feedback exchanged:

I felt apprehensive ahead of this session, as it was a complete re-design of some workshops I had previously delivered. The course leader had also asked me to open these workshops up to multiple year groups. With so many elements out of my control, I had spent a reasonable amount of time planning a session that could achieve the learning outcomes for a group of learners with a diversity of skill level and experience.

As a practitioner who is in the process of developing an identity as an educator, I found Johns insights very encouraging, enlightening, and clarifying. I felt delighted and enthused by this positive, generative feedback. The references shared were also very interesting to reflect upon, and have offered me more terminology with which to describe and discuss my pedagogic practice.

John’s use of the term ‘forensic’ is fascinating. On reflection, scientific methodologies are a significant part of my own approach to my craft, as well as a source of inspiration in teaching. I often discuss new materials, research methods, and innovations in sustainability with my brother, who is a Mechanical Engineer. The parallels between our disciplines in regard to these elements is surprisingly strong. This is something I would be interested in exploring further, as a way of unpacking historical, gendered assumptions around different disciplines within arts education, and how this reflects/permeates into professional practice.

The opening conversation around the BAFTA’s felt very natural, and I am interested in spending time considering the most effective ways of creating belonging in this way – I understand from Johns observation that it is equally possible to incite feelings of exclusion through an informal conversation like this.

I found John’s remark on the way in which the icebreaker highlighted the diversity in the room encouraging. Celebrating and respecting the value of diversity is essential to creative interdisciplinary practices, and is something I would like to draw attention to in every workshop I deliver in this space in the future.

Reflecting on Johns observations around the use of ‘data sheets’, I wonder if in future I could use some verbal prompts, or introduce the concept more comprehensively by showing examples from different disciplines. Alternatively, I could try drafting a ‘data form’ to further this idea of forensic investigation – though this may be too prescriptive, and dampen the expansive approach that the students took to this task.

Reflecting on John’s final comments, I have taken away a new appreciation for my own certainty in the abilities of the students to bring knowledge, creativity and expansive energy to the collaborative learning space.